You’ve built something meaningful. And yet, you’re scanning every meeting, every social gathering, every interaction for proof that you don’t belong. An imposter. Out of place. Here’s the uncomfortable truth: if you’re determined to find evidence you don’t belong, you’ll find it everywhere. Your brilliant, accomplished brain will turn every overlooked email, every awkward pause, every perceived slight into ammunition against yourself. This article isn’t about toxic positivity or pretending that belonging crises don’t exist. It’s about understanding why successful people are often the most skilled at prosecuting their own inadequacy—and what to do when you catch yourself building a case you were never meant to win.

Recommended TED talk of the month

This article is based on Bréné Brown’s The power of vulnerability – it is such a powerful message that I felt compelled to share part of it there.

So many of the things she says resonate strongly, in this video and in her book Braving the Wilderness: The Quest for True Belonging and the Courage to Stand Alone :

“True belonging is not passive. It’s not the belonging that comes with just joining a group. It’s not fitting in or pretending or selling out because it’s safer. It’s a practice that requires us to be vulnerable, get uncomfortable, and learn how to be present with people without sacrificing who we are. We want true belonging, but it takes tremendous courage to knowingly walk into hard moments.”

“True belonging is the spiritual practice of believing in and belonging to yourself so deeply that you can share your most authentic self with the world and find sacredness in both being a part of something and standing alone in the wilderness. True belonging doesn’t require you to change who you are; it requires you to be who you are.”

And here is a reminder of what Braving stands for: B boundaries R reliability A accountability V vault I integrity N non-judgement G generosity

5 Key Takeaways for the Time-Starved

- Your brain’s negativity bias is a feature, not a bug—but when misdirected, it turns normal social dynamics into evidence of your inadequacy.

- Belonging isn’t found; it’s created—and high-achievers have a unique opportunity to curate communities based on authenticity, not performance.

- The stories you tell yourself become your reality—and you’re currently narrating a tragedy when you could be writing an adventure.

- Vulnerability is the executive superpower no one taught you—admitting you’re struggling with belonging strengthens rather than weakens your authority.

- Purpose doesn’t depend on external validation—it emerges when you stop auditioning for approval and start acting from your core values.

Introduction: The Search Party for Evidence of Your Own Irrelevance

You’ve spent decades building something magnificent. A career that matters. A reputation that precedes you. Relationships that enrich your life. And now, standing in a conference room, at a dinner party, or scrolling through LinkedIn at midnight, you’re conducting an investigation worthy of a forensic accountant—except you’re gathering evidence for your own insignificance.

Did your colleague forget to copy you on that email? Evidence.

Did the conversation shift when you entered the room? Evidence.

Did someone younger get the project you wanted? More evidence.

Welcome to the high-achiever’s paradox: you’ve built genuine success, yet somehow you’ve convinced yourself you’re auditioning for a role in your own life—and failing the screen test.

Here’s what nobody tells you about belonging: the crisis isn’t about whether you actually fit in. It’s about the stories you’re telling yourself whilst you’re there. And if those stories sound like a prosecutor building a case against your worth, it’s time we talked.

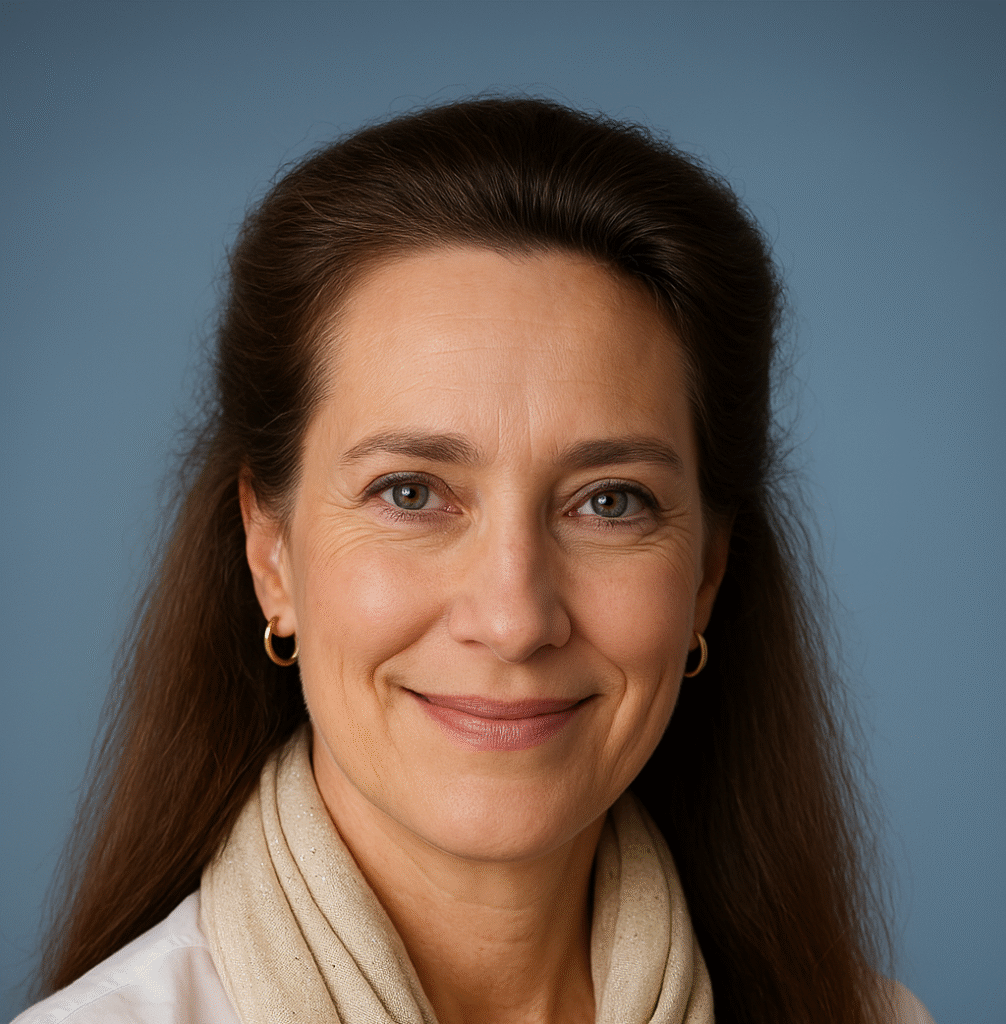

I’m Dr Margaretha Montagu—MBChB, MRCGP, NLP master practitioner, and medical hypnotherapist—and I’ve spent 20 years helping stressed executives and professionals navigate life’s crucibles, from unexpected illness to divorce to the peculiar loneliness that can accompany success. Over 15 years of hosting stress management retreats where guests walk the Camino de Santiago, and through 8 non-fiction books on coping with crises, I’ve observed a pattern: high-achievers are spectacularly good at finding evidence for whatever they’re looking for. When you’re looking for market opportunities, you find them. When you’re looking for operational inefficiencies, you spot them. And when you’re looking for proof you don’t belong? Well, you’ll find that too.

The question isn’t whether evidence exists. The question is: why have you hired yourself as prosecutor instead of defence counsel?

Amanda’s Story: The Woman Who Collected Proof

Amanda Stevens first noticed it at the quarterly board meeting.

She’d prepared meticulously, as always—the presentation polished, the financials watertight, her navy suit pressed with military precision. But as she clicked through her slides, she caught it: a micro-expression from James, the new CFO. Was that a smirk? Her throat tightened. She stumbled over a statistic she could usually recite in her sleep.

The meeting room suddenly felt vast. The recycled air tasted metallic, catching in her chest. She could hear the clock above the door ticking—or was that her heartbeat? The leather chair creaked as she shifted, and she was certain everyone noticed. The projector’s hum seemed accusatory. Her fingers, resting on the mahogany table, looked somehow exposed. Vulnerable.

She powered through, but the damage was done. In her mind, she’d filed it away: Evidence Item #1: They think I don’t belong here.

The pattern accelerated. At the industry conference, she introduced herself to a group discussing emerging markets. The conversation continued, but she felt it—that imperceptible shift in energy. Were they merely being polite? Evidence Item #2. At dinner with her husband’s colleagues, someone referenced a cultural moment she’d missed. She saw the glances. Evidence Item #3. Her assistant suggested a new project management system “that everyone’s using now.” The implication hung unspoken: You’re behind. Item #4.

Within three months, Amanda had compiled an impressive dossier. She’d become a barrister arguing for her own inadequacy, and she was winning every case.

The evidence manifested physically. Her shoulders hunched slightly when entering rooms. She second-guessed comments before making them, tasting the words for potential judgment before releasing them into the air. She touched her hair more, adjusted her clothes, checked her phone—physical tells of someone convinced they were being evaluated and found wanting.

At a client dinner, she ordered what the host ordered, rather than what she actually wanted. The Dover sole arrived, smelling of butter and lemon, but she barely tasted it. She was too busy monitoring—reading micro-expressions, tracking conversational flows, gathering more evidence. The restaurant’s ambient jazz felt too loud, too obvious. She was performing belonging rather than experiencing it.

Then came the evening that changed everything.

She was preparing for a keynote speech—a significant honour in her industry. She opened an old file on her laptop, searching for statistics. Instead, she found a folder of testimonials from people she’d mentored over the years. Emails. Cards. LinkedIn messages.

One stopped her cold. From Marcus, now a CEO himself: “Amanda, you taught me that leadership isn’t about having all the answers. It’s about asking the right questions. You belonged in every room because you brought your whole self—doubts included. That authenticity changed my career.”

She read it again. The words on the screen blurred slightly. She could smell the coffee growing cold beside her laptop, feel the rough texture of the old cardigan she wore when working from home—the one she’d never wear to the office because it wasn’t “professional” enough.

You belonged in every room because you brought your whole self.

When had she stopped doing that?

She thought about the board meeting. The real issue wasn’t James’s expression—which she’d likely misread. It was that she’d been so busy monitoring for signs of rejection that she’d disconnected from her own expertise. She’d brought a performance of Amanda rather than Amanda herself.

The conference conversation. She’d interpreted politeness as dismissal because she’d entered the group already convinced she was an outsider. Her discomfort had created a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The pattern became clear. She wasn’t finding evidence that she didn’t belong. She was creating it—through her own disconnection, her own self-surveillance, her own refusal to show up authentically.

At her next board meeting, she tried something radical. She brought herself. When she didn’t know an answer, she said so. When someone referenced something unfamiliar, she asked about it with genuine curiosity rather than shame. She let her enthusiasm for a new initiative show, even though it made her voice pitch higher with excitement—something she’d trained herself to control years ago.

Afterwards, James approached her. “That was refreshing,” he said. “Most people here are so guarded. It’s nice to see someone actually engage.”

Amanda smiled. Not the professional smile she’d perfected. A real one, that reached her eyes and made the skin crinkle at the corners.

She’d spent months collecting evidence of her inadequacy. Now she was discovering something else: belonging isn’t something you find. It’s something you create, by choosing to stop prosecuting yourself and start showing up.

In my storytelling circles, I’ve witnessed this transformation dozens of times. When we invite participants to share authentic stories—not curated versions of themselves—the room shifts. Shoulders drop. Breath deepens. People stop performing and start connecting. That’s where true belonging lives: in the vulnerable spaces between perfectly constructed narratives.

The Belonging Crisis

The question “Don’t walk through the world looking for evidence that you don’t belong, you’ll find it” speaks to something profound about human psychology and, paradoxically, about success itself.

The Neuroscience of Not Belonging

Our brains evolved with a powerful negativity bias—a survival mechanism that prioritised spotting threats over appreciating safety. In ancestral environments, the person who noticed the rustling grass (potential predator) survived more often than the person who admired the sunset. This bias remains hardwired.

For high-achievers, this mechanism often misfires spectacularly. Your accomplished brain, trained to identify problems and solve them, turns that analytical prowess inward. You become extraordinarily skilled at pattern recognition—but the patterns you recognise confirm your fears rather than your strengths.

When you walk into a room believing you might not belong, your reticular activating system—the brain’s attention filter—begins scanning specifically for confirming evidence. Neutral expressions become judgmental. Normal conversational pauses become pointed silences. Typical professional distance becomes personal rejection.

This isn’t weakness. It’s your brain doing exactly what you’ve trained it to do: find what you’re looking for.

The Achievement Paradox

Successful professionals face a unique belonging challenge. You’ve often achieved success by being hyper-aware of gaps—in markets, in strategies, in your own knowledge. This skill, so valuable professionally, becomes toxic when applied to social belonging.

Moreover, success can create isolation. As you advance, peer groups shrink. The vulnerability that creates genuine connection feels increasingly risky when you’re supposed to project authority. You become skilled at professional persona-management—so skilled that you forget how to simply be yourself.

Through my 15 years hosting Camino de Santiago retreats, I’ve observed a consistent pattern: executives and professionals arrive wearing their accomplishments like armour. They introduce themselves with titles and achievements. They perform competence even when learning to navigate unfamiliar terrain.

Then, usually around day three, something shifts. Someone admits they’re struggling with a blister. Another confesses they’re terrified of what they’ll return to. Someone else shares a story about failure rather than success. The armour cracks. And in those cracks, belonging grows.

The Storytelling Connection

Humans are narrative creatures. We don’t experience reality directly; we experience the stories we tell ourselves about reality. When you narrate your life as a story of not belonging, you unconsciously seek plot points that confirm that narrative.

Consider Amanda’s story. The “evidence” she collected—a facial expression, a conversational shift, a suggestion about new technology—was narratively neutral. These moments became “evidence” only because she was writing a story called “I Don’t Belong.” Had she been writing a different story—”I’m Learning and Growing” or “I’m Navigating New Challenges”—the same events would have different meanings entirely.

This is why my storytelling circles prove so transformative. When participants hear others’ authentic stories, they recognise their own narrative patterns. They see how they’ve been curating their life story to prove a point—often a point that diminishes them.

The power of reframing isn’t about positive thinking. It’s about recognising you’re already writing fiction. The question is whether you’re writing tragedy or adventure.

The Social Architecture of Belonging

Belonging isn’t passive. It’s not something bestowed upon you by others’ acceptance. It’s actively created through three key practices:

Authentic self-presentation: Bringing your actual self—doubts, enthusiasms, quirks included—rather than a carefully curated version designed to pre-empt judgment.

Generous interpretation: Choosing to interpret ambiguous social cues through a lens of curiosity rather than fear. That colleague who didn’t greet you warmly might be distracted, tired, or dealing with their own insecurities—not judging you.

Contribution from core values: Belonging deepens when you contribute what matters to you, rather than what you think others expect. When you show up aligned with your values, you attract genuine connection rather than performing for approval.

With over 40 guest testimonials on my website from retreat participants and clients who’ve navigated these challenges, one theme recurs: belonging emerged when they stopped trying to deserve it and simply claimed it.

Why This Matters Beyond the Individual

The belonging crisis among successful professionals isn’t merely personal—it’s cultural and organisational. When leaders feel they must perform belonging rather than experience it, they create workplace cultures where everyone else must do the same. Authenticity becomes risk. Vulnerability becomes weakness. Connection becomes transactional.

This creates organisations where everyone is performing, no one is connecting, and innovation suffers. Because genuine innovation requires the psychological safety to propose ideas that might fail, to admit confusion, to ask “stupid” questions. When belonging feels conditional on flawless performance, creativity dies.

The professionals who break this pattern—who model authentic self-presentation despite insecurity—transform entire cultures. They give others permission to stop prosecuting themselves. They create spaces where belonging becomes about contribution rather than perfection.

This is why addressing your own belonging crisis isn’t self-indulgent. It’s leadership. It’s changing the story—not just yours, but everyone’s who watches how you show up.

A Powerful Writing Prompt

These prompts are designed to help you examine your own patterns of evidence-gathering and rewrite your belonging narrative:

Prompt The Evidence Dossier

Time needed: 20 minutes

Create two columns on a page. Label the left “Evidence I Don’t Belong” and the right “Alternative Interpretations.”

In the left column, list specific instances where you felt you didn’t belong. Be concrete: what happened, where, when, who was involved. Notice sensory details—what you saw, heard, felt.

Now, in the right column, write at least three alternative interpretations for each piece of “evidence.” Force yourself to imagine neutral or positive explanations. That colleague who didn’t make eye contact might have been preoccupied with a sick child. That awkward pause might have been thoughtful consideration, not judgment.

The goal isn’t to convince yourself the positive interpretations are “true”—it’s to recognise that your negative interpretations aren’t definitively true either. You’re always interpreting. The question is whether your interpretations serve you.

Further Reading: Five Unconventional Books on Belonging

These aren’t the typical self-help books you’d expect. Each offers a distinctive lens on belonging that challenges conventional wisdom:

1. “The Art of Gathering” by Priya Parker

Why this book: Most belonging books focus on how to fit into existing structures. Parker flips this, exploring how we create the spaces where belonging happens. As someone who’s led people to gather around vulnerable storytelling for years, I find her framework revolutionary: belonging isn’t about you adapting to others’ spaces—it’s about creating spaces where authentic connection becomes inevitable. For executives who feel they don’t belong, this book offers an unexpected solution: stop trying to fit in and start creating gatherings aligned with your values.

2. “Man’s Search for Meaning” by Viktor Frankl

Why this book: Frankl, surviving Nazi concentration camps, discovered that belonging isn’t about external circumstances—it’s about meaning. In the most belonging-hostile environment imaginable, those who found purpose survived psychologically. For high-achievers struggling with belonging, this book offers crucial perspective: you’re seeking belonging in the wrong place. When you’re contributing something meaningful, belonging becomes a byproduct rather than a goal. Frankl’s logotherapy principles have profoundly influenced my approach to stress management and crisis navigation.

3. “The Gifts of Imperfection” by Brené Brown

Why this book: Brown’s research confirms what I’ve observed in countless storytelling circles: belonging requires vulnerability, which requires accepting imperfection. For professionals trained to project competence, this is revolutionary and terrifying. Brown doesn’t offer easy answers—she challenges the perfectionism that blocks genuine connection. Her exploration of shame and worthiness speaks directly to the belonging crisis among successful people who believe they must earn the right to belong.

4. “Finite and Infinite Games” by James P. Carse

Why this book: Carse’s philosophical exploration of two types of games—finite (played to win) and infinite (played to continue play)—illuminates why successful people often struggle with belonging. We’ve been treating belonging as a finite game: something to win through achievement and perfect performance. Carse suggests belonging might actually be an infinite game: not something you win, but something you participate in. This reframe has transformed how I approach stress management—moving from “fix the problem” to “engage with the process.”

5. “The Anthropology of Turquoise” by Ellen Meloy

Why this book: Meloy’s meditation on colour, landscape, and perception seems an odd choice for a belonging book—until you realise it’s fundamentally about how we see. She explores how perception shapes reality, how we see what we’re trained to see. For someone looking for evidence they don’t belong, Meloy offers a master class in seeing differently. Her lyrical prose demonstrates that belonging isn’t about the external world changing—it’s about perceiving what was always there. This resonates deeply with my Camino retreats, where walking through landscape transforms how participants see themselves.

P.S. My book “Embracing Change – in 10 minutes a day” offers practical, daily exercises for navigating transitions and uncertainty. While not specifically about belonging, it addresses the core challenge underneath: managing the discomfort of not-knowing, of being between identities, of existing in liminal spaces where belonging feels uncertain. Available through my website.

From the Camino

“I arrived at Dr Montagu’s Camino retreat having just been passed over for a partnership position I’d worked towards for eight years. I was convinced I’d been found wanting—too soft, too emotional, too something. I brought this story with me to France, wearing it like a hair shirt.

On day four, walking through autumn mist, Dr Montagu asked me a simple question: ‘Why are you looking for evidence?’ I realised I’d spent months collecting proof of my inadequacy, interpreting every interaction through that lens. That partnership decision had become the headline of a story I was writing about not belonging—in my firm, in my profession, in my own ambition.

The storytelling circles changed everything. Hearing other successful professionals share their belonging struggles, I recognised we were all prosecuting ourselves with the same fervour we brought to our work. Dr Montagu’s gentle questions helped me see I’d been asking the wrong thing. Not ‘How do I prove I belong?’ but ‘What would I contribute if I stopped auditioning?’

I returned home and resigned from that firm. I joined a smaller practice aligned with my values. I belong there—not because they accept me despite my flaws, but because I stopped looking for evidence I needed to hide them. The Camino didn’t fix me. It helped me stop breaking myself.”

— Jennifer K., Corporate Lawyer, London

From a Storytelling Circle

“Dr Montagu’s storytelling circles taught me something my MBA never did: authentic stories create belonging in ways polished presentations never can. I’d spent my career crafting the perfect professional narrative—achievements without struggles, confidence without doubt. It made me successful. It also made me profoundly lonely.

In the storytelling circle, I shared a story about failing spectacularly—a product launch disaster that nearly ended my career. I’d never told anyone the full, messy truth. As I spoke, I saw recognition in others’ faces. Not judgment. Recognition. Afterwards, a retired executive—someone I’d been slightly intimidated by—shared his own failure story. Then another participant. Then another.

We weren’t bonding over success. We were bonding over truth. Dr Montagu’s approach isn’t about forced vulnerability or artificial team-building. It’s about creating space where you can stop curating and start connecting. That’s where belonging actually lives—in the space between our polished stories and our true ones.”

— Michael T., Technology Executive, Manchester

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Isn’t looking for evidence I don’t belong just realistic self-assessment? Shouldn’t successful people stay alert to how they’re perceived?

There’s a crucial difference between genuine feedback and confirmatory bias. Realistic self-assessment involves seeking diverse input, considering context, and maintaining perspective. Looking for evidence you don’t belong is selective attention that ignores contradictory data. It’s the difference between “Let me understand how others experience me” and “Let me prove I’m inadequate.” One creates growth; the other creates suffering. Your brain can’t distinguish between them—you must consciously choose which investigation you’re conducting.

Q: What if the evidence is actually real? What if I genuinely don’t belong in certain spaces?

Sometimes you don’t belong—and that’s data, not verdict. Not belonging in a specific context doesn’t mean you don’t belong anywhere. A fish doesn’t belong in a tree, but that says nothing about the fish’s worth. The question isn’t “Do I belong here?” but “Is this where I want to belong?” Successful people often confuse achievement with alignment. You might not belong in that role, that culture, that relationship—not because you’re inadequate, but because it’s not your space. The crisis comes when you interpret contextual misalignment as global inadequacy.

Q: How do I stop this pattern when it feels so automatic? The evidence-gathering happens before I even notice I’m doing it.

This is where NLP and hypnotherapy principles prove invaluable. The pattern operates below conscious awareness, which is why intellectual understanding doesn’t stop it. You need to interrupt the pattern at a neurological level. Start by naming it when it happens: “I’m gathering evidence again.” This creates a split-second pause between stimulus and response. In that pause, ask: “What else could this mean?” You’re not trying to stop the pattern entirely—you’re inserting choice into what was previously automatic. Over time, this rewires the neural pathway. It’s the same principle I use in stress management: you can’t stop stress responses, but you can create space between trigger and reaction.

Q: Isn’t this just positive thinking? Are you suggesting I ignore real problems?

Absolutely not. Positive thinking tries to paste happy narratives over negative ones. This is about recognising you’re always interpreting, always creating narratives, and those narratives aren’t neutral observations—they’re creative acts. You’re not ignoring problems; you’re questioning your interpretation of what constitutes a problem. When you interpret a colleague’s distraction as evidence you’re boring, you’ve created a problem that didn’t exist. When you interpret the same distraction as… distraction, you’ve saved yourself unnecessary suffering. This isn’t optimism; it’s accuracy.

Q: What if changing this pattern makes me complacent? Doesn’t this insecurity drive my success?

This is the fear that keeps many high-achievers trapped in self-prosecution. But examine it: Has looking for evidence you don’t belong made you more successful, or just more anxious? There’s a difference between healthy striving and toxic self-monitoring. Healthy striving says: “I want to improve this skill.” Toxic self-monitoring says: “Everyone’s noticing I’m inadequate.” One creates growth; the other creates paralysis. Your achievements came despite this pattern, not because of it. Imagine your capabilities without the constant self-prosecution tax. That’s not complacency; that’s unleashing your actual potential.

Conclusion: Choosing Your Investigation

Here’s what I’ve learned from two decades of working with stressed, successful professionals, from guiding hundreds through the transformative walking meditation of the Camino, from facilitating storytelling circles where masks drop and truth emerges:

You will always find what you’re looking for.

Your brilliant, pattern-recognising, problem-solving brain is a magnificent instrument. When you direct it to find evidence of your inadequacy, it will deliver a comprehensive case file. When you direct it to find evidence of your capacity, contribution, and authentic connection, it will deliver that too.

The evidence doesn’t change. Your investigation does.

Belonging isn’t something you discover—it’s something you create through the stories you tell, the interpretations you choose, and the courage to bring your authentic self rather than your performed self.

Amanda Stevens—and the Jennifers and Michaels who’ve walked my Camino trails and shared their stories in circles lit by French sunset—didn’t find belonging. They stopped looking for evidence they didn’t deserve it. In that pause, in that radical act of stopping the prosecution, belonging emerged.

Not because the world changed. Because they stopped seeing themselves through the prosecution’s eyes and started seeing themselves through their own.

You belong. Not because I say so, but because belonging isn’t bestowed—it’s claimed. The question isn’t whether you belong. The question is whether you’ll stop gathering evidence against yourself long enough to notice you were always home.

Come and Walk the Camino: An Invitation

There’s something about walking that bypasses the mind’s usual defences. Something about ancient pilgrimage routes that strips away the performed self and reveals what lies beneath. Something about the rhythm of footsteps, the simplicity of the task—left foot, right foot, breathe—that quiets the prosecutorial voice long enough to hear something truer.

My Camino de Santiago stress relief hiking retreats in the south-west of France offer exactly this: a chance to walk yourself home to belonging, not through positive thinking or forced revelations, but through the embodied experience of moving through landscape whilst your internal landscape shifts.

These aren’t typical walking holidays. Yes, you walk sections of the ancient Camino route, through forests and vineyards, medieval villages and rolling hills. But we also practise mindfulness and meditation exercises specifically designed for stress management—techniques I’ve refined over 15 years of guiding executives and professionals through exactly the belonging crisis you’re experiencing.

We gather for storytelling circles where you’ll share and hear authentic narratives—not the polished versions we present professionally, but the true, messy, vulnerable stories where real connection lives. And yes, my Friesian horses (Twiss and Zorie) and Falabella ponies (Loki and Lito) join us, offering their unique form of present-moment awareness and non-judgmental companionship that often unlocks what words cannot.

These retreats aren’t about fixing you—you’re not broken. They’re about creating the conditions where you stop prosecuting yourself long enough to remember who you actually are beneath the accumulated evidence of inadequacy you’ve been carrying.

The Camino has been transforming pilgrims for over a thousand years. Not through dramatic revelations, but through the simple, profound act of walking whilst carrying less—literally and metaphorically.

Perhaps it’s time to put down the evidence dossier you’ve been compiling against yourself. Perhaps it’s time to walk toward belonging rather than away from imagined rejection.

PS. I am working on an online retreat that will help people cope with the grief caused by the loss of a horse – it is similar to losing any loved one, but also different. The need to belong was intense as I tried to come to terms with the loss of my soulmare Belle, and this video helped me to get everything into perspective. As you may know, what I am best at is helping people through life transitions, and the loss of someone we love certainly falls in this category. Creating this online retreat is difficult, but I’m persevering, as I am learning so much by doing this. I find myself spending much more time just being with the herd, and I wrote this post about the comfort I received from the horses I have left:

The Compassionate Insight-giving Guide to Getting Over the Loss of Your Horse – an Online Course – find support, guidance, and practical tools to navigate the complex emotions and challenges associated with the loss of a heart horse. Get immediate access

“I am an experienced medical doctor – MBChB, MRCGP, NLP master pract cert, Transformational Life Coach (dip.) Life Story Coach (cert.) Stress Counselling (cert.) Med Hypnotherapy (dip.) and EAGALA (cert.) I may have an impressive number of letters after my name, and more than three decades of professional experience, but what qualifies me to excel at what I do is my intuitive understanding of my clients’ difficulties and my extensive personal experience of managing major life changes using strategies I developed over many years.” Dr M Montagu