Why the Most Successful People Struggle Most with Liminal Spaces (And What to Do About It)

What this is: A deep dive into why we find “in-between” moments excruciating, what anthropology teaches us about transformation, and how to stop filling every gap with frantic action.

What this isn’t: Another productivity hack, a call to “embrace the grind,” or advice to simply “be patient.” (If one more person tells you to journal about it…)

Read this if: You’ve ever stood in your kitchen at 3am wondering who you’re becoming, filled every silence with a new project, or felt genuine panic at the thought of not having a plan.

Time investment: 19 minutes that might save you years of running from the very spaces where transformation happens.

Five Key Takeaways for the Perpetually Productive

- Liminal spaces aren’t empty—they’re generative. The discomfort you feel isn’t weakness; it’s your psyche doing the deep work of reconstruction.

- Your leadership skills become liabilities here. The decisiveness that built your career will sabotage your transformation if you can’t resist the urge to “fix” the unknown.

- Community changes when you change. Your metamorphosis creates permission for others to enter their own in-between spaces.

- The body knows before the mind. Physical practices (walking, especially) allow processing that cognitive approaches can’t touch.

- There’s a map for this territory. Anthropologists have studied these transitions for over a century—you’re not lost, you’re precisely where this transformation requires you to be.

Introduction to Liminal Spaces

Did you know that success makes you absolutely rubbish at waiting?

Stress destroys Lives. To find out what you can do to safeguard your sanity by taking my insight-giving quiz, subscribe to my mailing list.

You’ve spent decades building a life where decisiveness is currency, where speed matters, where “I don’t know” feels like professional suicide. You’ve trained yourself to see problems as puzzles with solutions, uncertainty as something to eliminate rather than inhabit.

Then life cracks open—redundancy, divorce, illness, the death of someone who shaped you, the slow-dawning realisation that the life you built doesn’t fit anymore—and suddenly you’re standing in a hallway with no map, no timeline, and no bloody idea which door to open next.

Your brain, that magnificent executive function machine, goes into overdrive. New business venture? Relationship? City? Identity? Pick one. Any one. Just pick something so we can stop this excruciating not-knowing.

But what if standing in the hallway itself is the point?

What if these liminal spaces—these maddening, destabilising thresholds between one version of yourself and the next—aren’t obstacles to overcome but crucibles where the most profound transformations happen?

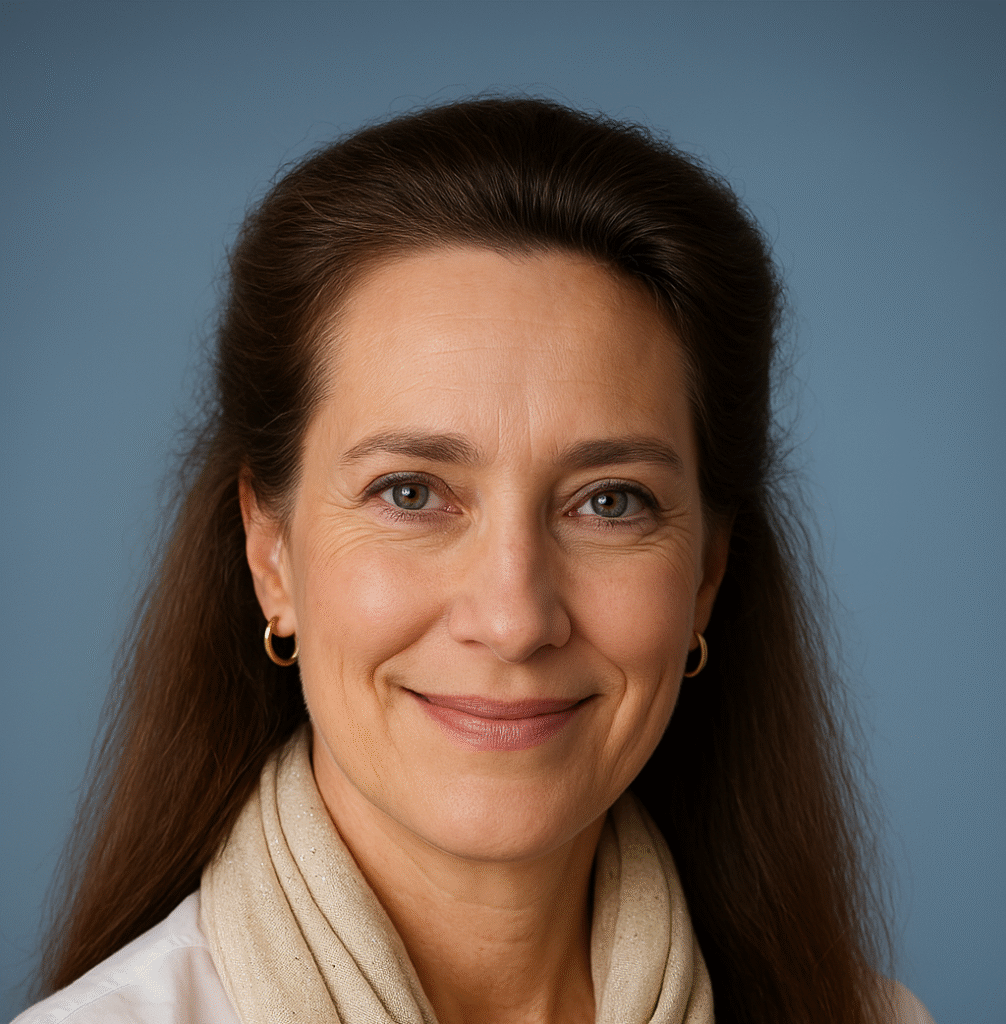

I’m Dr Margaretha Montagu, and I’ve spent twenty years as a GP watching high-functioning people unravel in these in-between moments, fifteen years hosting stress management retreats where executives walk the Camino de Santiago and discover that sometimes you have to move your body to shift your life, and countless hours in storytelling circles where the bravest thing anyone does is admit: I don’t know who I’m becoming, and it’s terrifying.

This isn’t theory. This is earned knowledge from my own relationships, from writing eight books about loss and transition, from holding space for dozens of guests who arrived at my retreats running from the very stillness they most needed.

Let me tell you about Corinne.

Corinne Smith and the Conference Room Cage

The air conditioning in the Zürich boardroom hummed the same note it had for seven years. Corinne could feel the vibration through her leather chair, a frequency she’d stopped consciously hearing around year three.

She pressed her nails into her palms—a habit she’d developed during particularly tedious presentations—and watched her managing director’s lips move. The words came from very far away: “restructuring,” “strategic realignment,” “your contribution has been invaluable.”

Corinne’s coffee had gone cold. She could see the film forming on its surface, iridescent and oily, catching the LED lights overhead. Her hands, she noticed with curious detachment, were completely steady. She’d given that presentation on Q3 projections just two hours ago. Had delivered it brilliantly, in fact. The numbers had been unassailable.

“We’d like to offer you a generous redundancy package,” the HR director was saying now, sliding a cream folder across the table. The folder made a whisper of sound against the wood. Corinne found herself fixated on that sound — so very final.

In the lift going down twenty-three floors, she caught her reflection in the polished steel doors. The woman looking back wore a Jil Sander suit Corinne couldn’t really afford, carried a Tumi briefcase with a broken interior pocket she’d been meaning to repair for months, and had eyes that looked… wait, was that relief?

That night, Corinne sat on her balcony overlooking Lake Zürich and felt the May wind coming off the water, sharp enough to bite despite the warming season. She’d poured a glass of the Sancerre she’d been saving—for what, exactly?—and taken one sip before setting it down.

The city hummed below her: trams clanging, voices rising and falling in German and English and Italian, the thick smell of someone grilling bratwurst mixing with the mineral scent of the lake. She’d lived in this flat for six years, had learned which neighbours played piano on Thursday evenings and which ones argued in whispered French on Sundays, but sitting there she realised she’d never simply been here. Never sat without her laptop, without a conference call, without mentally reviewing tomorrow’s agenda.

The wind lifted a strand of hair across her face. She didn’t brush it away.

Three weeks later, she still hadn’t applied for a single position. Her LinkedIn profile sat dormant while recruiters’ messages piled up like unopened post. Her mentor left increasingly concerned voicemails: “Corinne, you’re one of the most talented strategists I know. Why aren’t you leveraging this moment?”

Why indeed?

She’d started walking. Not the purposeful stride from U-Bahn to office, but aimless wandering through neighbourhoods she’d glimpsed only from taxi windows. She discovered a Turkish café where the owner made çay so strong it could wake the dead, served in tulip-shaped glasses that burned her fingertips. She learned to say teşekkür ederim—thank you—and meant it in a way she hadn’t meant anything in years.

One morning, standing in a small park watching a father teach his daughter to ride a bicycle—the child’s laughter piercing and pure as she wobbled and recovered, wobbled and recovered—Corinne felt something crack open in her chest. Not grief, exactly. Not joy. Something rawer, more primal.

She’d spent fifteen years becoming the youngest VP in her company’s European division. Had sacrificed relationships, health, the novel she’d dreamed of writing at twenty-five. Had built a life that looked, from the outside, like unqualified success.

And she’d been absolutely, crushingly miserable for at least seven of those years.

The realisation didn’t arrive as a dramatic revelation but as something she’d known all along and had been too frightened—or too busy—to acknowledge. The redundancy hadn’t taken her job. It had removed the scaffolding that had been the only thing holding up a structure that was, she could see now, already collapsing.

Sitting in that park, with the smell of cut grass sharp in her nose and the sun warm on her closed eyelids, with the distant sound of the child’s delighted squeals and the closer sound of her own breath, Corinne understood something: she wasn’t lost. She was right where she needed to be. In the terrifying, exhilarating space between who she’d been and who she might become.

Her hands shook as she pulled out her phone and, instead of checking email, texted her sister in Cape Town: “I think I need to get away for a while.”

The reply came immediately: “About bloody time.”

For the first time in seven years, Corinne laughed until tears streamed down her face.

The Anthropology of Becoming: Understanding Liminal Spaces

The term “liminal” comes from the Latin limen, meaning threshold. Anthropologist Arnold van Gennep introduced the concept in 1909, studying rites of passage across cultures, but it was Victor Turner who, in the 1960s, truly illuminated what happens in these betwixt-and-between spaces.

Turner observed that liminal periods—whether in tribal initiation ceremonies or modern life transitions—share distinct characteristics. The normal rules don’t apply. Social hierarchies temporarily dissolve. The person in transition exists in a state of “structural invisibility”—neither who they were nor who they’re becoming.

For high-achievers, this is absolutely maddening.

You’ve built your identity on productivity, clarity, and forward momentum. Your professional value rests on your ability to assess, decide, and execute. Suddenly, you’re in a space where none of those skills help. Worse, they actively hinder the process.

Because here’s what the research shows: liminal spaces are supposed to be disorienting. That disorientation isn’t a sign you’re doing it wrong—it’s evidence that deep psychological reorganisation is happening. Your psyche is dismantling old structures to make room for new ones. That’s not comfortable work.

We respond to this discomfort by rushing into the next thing: the rebound relationship, the hasty career pivot, the geographic cure. I’ve learned to recognise the subtle ways we resist the very stillness that could transform us.

Hosting Camino de Santiago walking retreats, I’ve witnessed something remarkable: when you put the body in motion through beautiful landscape, the mind paradoxically finds the stillness it’s been fleeing. There’s something about the rhythm of walking—especially multi-day pilgrim walking—that allows processing to happen below the level of conscious thought.

The guests who arrive at my retreats in the south-west of France are typically running from something: a ended marriage, a cancer diagnosis, a career that stopped making sense. They expect I’ll help them “figure it out.” Instead, I invite them to stop figuring. To walk. To sit with my horses (especially Loki, and Lito have a gift for presence that humans struggle to match). To tell stories in circles where the only goal is witnessing, not solving.

What happens in these liminal spaces—whether on the Camino or in the quiet of your own kitchen at 3am—is that you stop performing competence and start discovering authenticity. The mask you’ve worn, sometimes for decades, begins to slip. And underneath? Often something truer, more vital, more aligned with who you actually are rather than who you thought you should be.

This transformation ripples outward. When you give yourself permission to not know everything right away, you create space for others to do the same. Your children see that uncertainty doesn’t equal failure. Your colleagues notice that strength can include vulnerability. Your friends gain permission to question their own unexamined assumptions.

I’ve written eight books about navigating unexpected transitions—divorce, loss, illness, crisis—and the through-line in all of them is this: the people who try to speed through liminal spaces end up returning to them, often more painfully. The people who learn to temporarily inhabit the threshold, to let themselves be genuinely undone before reassembling, emerge with lives that actually fit them.

That’s not mystical thinking. That’s what forty-plus testimonials on my website reflect: transformation requires a willingness to temporarily not know what’s next, and that willingness is, for most successful people, the hardest work they’ll ever do.

Writing Prompt: Owning Your Threshold

Set a timer for fifteen minutes. Find somewhere you won’t be interrupted (harder than it sounds, I know).

Write, by hand if possible, a letter to yourself from the perspective of the liminal space itself. Let the threshold speak. What does this in-between place want you to know? What is it protecting you from rushing past? What gifts is it holding that you can only receive if you stay?

Don’t edit. Don’t make it sensible. Let it be strange, contradictory, raw. The point isn’t a finished product—it’s accessing the wisdom that your relentlessly productive mind usually drowns out.

When the timer goes off, read what you’ve written. What surprised you? What made you uncomfortable? Those are probably the truths you most need to hear

Further Reading: Five Unconventional Books for the Liminal Space

1. The Liminality of Journeying: Internal and External Trips by Hazel Tucker (Editor)

Why this one: Unlike most self-help approaches, Tucker’s academic collection treats liminal space as worthy of rigorous study rather than something to overcome. For intellectually-minded readers who need permission to stop trying to “fix” their uncertainty, this book offers a framework that honours complexity. It’s dense, occasionally frustrating, and utterly illuminating for those who need to understand the “why” before accepting the “how.”

2. Transitions: Making Sense of Life’s Changes by William Bridges

Why this one: Bridges distinguishes beautifully between change (external, circumstantial) and transition (internal, psychological). His “neutral zone” is another way of describing liminal space, and his decades of working with organisations gives this book a practical grounding that speaks to professional readers. Warning: it will make you realise how many transitions you’ve rushed through, which might sting.

3. The Creative Tarot: A Modern Guide to an Inspired Life by Jessa Crispin

Why this one: Bear with me—I know tarot cards make some people twitchy. But Crispin’s book isn’t about fortune-telling; it’s about using archetypal images to access non-linear thinking. For people whose lives are dominated by logic and productivity, this offers a side door into intuitive wisdom. The liminal space demands different tools. This book provides some unexpected ones.

4. M Train by Patti Smith

Why this one: This isn’t a how-to book; it’s a meditation on loss, wandering, and the creative power of aimlessness. Smith writes about her own liminal spaces—after her husband’s death, between projects, in the gaps of daily life—with such exquisite attention that you begin to see your own in-between moments differently. For readers who resist self-help but respond to art, this is transformative medicine disguised as a memoir.

5. The Dip: A Little Book That Teaches You When to Quit (and When to Stick) by Seth Godin

Why this one: Counterintuitive choice, perhaps, but Godin’s short book addresses something crucial: not all thresholds lead somewhere you want to go. Some liminal spaces require deciding to walk away entirely. For achievers prone to powering through everything, this book gives permission to discern between a generative threshold and a dead end. That discernment is its own skill.

P.S. My own book, Embracing Change – in 10 Minutes a Day, offers a practical, accessible companion for anyone navigating unexpected transitions. It won’t tell you what to do—instead, it gives you tools to find your own answers, ten minutes at a time. Because transformation doesn’t require grand gestures. It requires showing up, daily, to the work of becoming.

Voices from the Threshold

Sarah T., Management Consultant, London Camino de Santiago Walking Retreat

“I arrived in France absolutely certain I was there to ‘sort myself out’ after my divorce. I had a timeline: one week to process, grieve, and emerge with a plan. Dr Montagu took one look at me and said, ‘What if you don’t manage to sort anything out at all?’ I nearly left immediately.

Instead, I walked. Day after day through vineyards and villages, no agenda beyond putting one foot in front of the other. And somewhere around day four, walking in silence, I realised I’d been running from the not-knowing for two years. The retreat didn’t give me answers. It gave me permission to stop demanding them.

Three months later, I still don’t have my life ‘figured out.’ But I’m not terrified anymore. The horses—particularly Twiss, who seemed to sense my anxiety before I felt it—taught me that presence doesn’t require certainty. That’s changed everything.”

Elena M., Entrepreneur, Amsterdam Virtual Storytelling Circle Participant

“I joined the storytelling circle reluctantly, as part of a leadership course. I’m Dutch—we’re not known for emotional vulnerability. But the format is clever: you tell a story from your life, the group witnesses without advice or fixing, and somehow that simple act cracks something open.

When I shared about the liminal space between selling my business and knowing what came next, I expected judgment for not having a plan. Instead, three other members said, ‘Same here.’ We’ve become each other’s permission to not know. The circle meets monthly, and it’s become the one place where I don’t have to perform competence. That space has made me a better leader, actually—less rigid, more human. Who knew vulnerability was a competitive advantage?”

Five Razor-Sharp FAQs

Q: How long will I be stuck in a liminal space, and how do I know when I’ve “emerged”?

There’s no standard timeline, which I know is maddening for planners. Some thresholds last weeks; others, years. You’ll know you’ve emerged not because you have all the answers, but because the uncertainty stops feeling like an emergency. The shift is subtle—one day you notice you’re acting from clarity rather than reacting from fear.

Q: I’m supporting someone through a liminal space. How can I help without trying to fix them?

Ask questions. Offer presence, not solutions. “What’s it like for you right now?” is infinitely more helpful than “Have you considered…?” Resist the urge to fill their silences with advice. Your discomfort with their uncertainty is your work to manage, not theirs to alleviate.

Q: What if my liminal space is financially precarious? I can’t afford to “find myself” for months.

Absolutely fair. Liminal space doesn’t require quitting your job or radical external change. Some of the deepest threshold work happens while you’re still showing up daily to responsibilities. The question isn’t whether you maintain income—it’s whether you can resist filling every gap with frantic activity. Can you create small pockets of not-knowing within a structured life?

Q: This sounds suspiciously like glorifying indecision. How is this different from just being stuck?

Brilliant question. Stuck feels dead, circular, like treading water. Liminal feels alive, uncertain, like standing at the edge of something. Stuck resists. Liminal allows. If you’re genuinely stuck, you know it—there’s a dull, repetitive quality. If you’re liminal, it’s uncomfortable but generative. Still unsure? Try engaging actively with the space (walking, writing, talking) and notice what shifts.

Q: I’ve been in transition for years. At what point should I just make a bloody decision?

Sometimes the liminal space reveals that you’re waiting for external permission you need to give yourself. Or you’re mistaking “not knowing the perfect path” for “not knowing enough to take a step.” Here’s a test: if someone told you that you couldn’t fail, what would you choose? If an answer surfaces immediately, that’s your intuition trying to break through the committee of fears. Trust it.

Conclusion: The Courage to linger on the Threshold

Standing in the hallway between lives is not where you wanted to be. I understand. You’ve spent decades building the skills to avoid exactly this kind of uncertainty.

But here you are anyway.

Here’s what I’ve learned, from my own unexpected transitions and from holding space for hundreds of others navigating theirs: the people who try to sprint through these thresholds almost always end up circling back, forced to do the work they tried to skip. The people who find the courage to stay—to be genuinely undone, to not know, to let the hallway reshape them—emerge as more truthful versions of themselves.

Not better. Not fixed. More real.

Your highest achievement might not be the career you built or the challenges you conquered. It might be this: learning to stand in the terrifying in-between spaces and let yourself be transformed rather than armoured.

The hallway isn’t empty. It’s full of possibilities you can only access by staying long enough to see what it offers.

You’re not lost. You’re exactly where transformation requires you to be.

And you don’t have to do it alone.

An Invitation to Pause on the Threshold

The Camino de Santiago has been calling seekers into liminal space for over a thousand years. There’s something about walking day after day through changing landscapes—your body in motion, your mind gradually quieting—that allows transformation to happen without forcing it.

My Camino de Santiago Crossroads Retreat in the south-west of France offers a rare thing: permission to not have answers. Over six days, you walk sections of the ancient pilgrim route through vineyards, forests, and medieval villages. We practice mindfulness and meditation designed specifically for stress management—not to “fix” you, but to create space for whatever wants to emerge.

The retreat includes storytelling circles, both with fellow walkers and with my small herd. There’s something about sharing your story with a horse standing peacefully beside you, offering no judgment and no advice, that strips away pretence. The horses don’t care about your CV. They respond to who you are right now, in this moment, threshold and all.

This isn’t a wellness retreat promising to optimise your performance. It’s an invitation to step off the treadmill of constant productivity and discover what happens when you finally give yourself permission to be uncertain. To walk without knowing where you’re going. To tell your story without needing to have the ending figured out.

Small groups mean genuine connection. The rhythm of daily walking means your body processes what your mind can’t. The ancient energy of the Camino means you’re joining a tradition of seekers who’ve walked these paths for centuries, all looking for what can only be found in the liminal space between leaving and arriving.

If you’re standing in your own hallway right now, wondering if you have to figure it all out before you can move, consider this: sometimes the way forward is to walk, literally, into the uncertainty. To let your feet find the path your mind can’t yet see.

The Camino has a saying: The way is made by walking.

Perhaps it’s time to begin.

Foundations for Your Future Protocol – a fast-paced, high-impact, future-focused course that facilitates the construction of identity-shaping stories about your future self so that you can make the changes needed to avoid having to go through big life changes again and again—without needing to process your past in depth and in detail.

“I am an experienced medical doctor – MBChB, MRCGP, NLP master pract cert, Transformational Life Coach (dip.) Life Story Coach (cert.) Stress Counselling (cert.) Med Hypnotherapy (dip.) and EAGALA (cert.) I may have an impressive number of letters after my name, and more than three decades of professional experience, but what qualifies me to excel at what I do is my intuitive understanding of my clients’ difficulties and my extensive personal experience of managing major life changes using strategies I developed over many years.” Dr M Montagu